This article includes additional highlighted information not found in the video.

This is the third installment of a three-part series on dogs in antiquity.  First we explored the ancient hairless breeds of the New World, including the popular ceramic funerary effigy of the Colima dog from a couple thousand years ago, and we met Sputnik, my awesome, little, hairless Xoloitzcuintli-Chihuahua puppy (okay, he’s 5 years old). Then we traveled to ancient China to look closely at an expressive mastiff figurine from the Han dynasty.

First we explored the ancient hairless breeds of the New World, including the popular ceramic funerary effigy of the Colima dog from a couple thousand years ago, and we met Sputnik, my awesome, little, hairless Xoloitzcuintli-Chihuahua puppy (okay, he’s 5 years old). Then we traveled to ancient China to look closely at an expressive mastiff figurine from the Han dynasty.  We learned a little about the roles of dogs in oracles, sacrifice, and the culinary scene (egad!) and read a bit of the Toa Te Ching talking about straw dogs. Now we’re heading home to the Classical World to consider the importance of dogs in ancient Greece and Rome.

We learned a little about the roles of dogs in oracles, sacrifice, and the culinary scene (egad!) and read a bit of the Toa Te Ching talking about straw dogs. Now we’re heading home to the Classical World to consider the importance of dogs in ancient Greece and Rome.

Perhaps the most heartfelt and memorable appearance of a dog coming to us from Greek antiquity is found in Homer’s Odyssey. In Book 17, toward the end of the poem, after 20 years away from home, after the epic slaughter at the fields and citadel of Troy, after the seemingly endless wanderings and adventures on the wine-dark sea, our eponymous hero Odysseus, king of Ithaca, disheveled and unrecognized, finally returns home. Unrecognized by all but one, his ever-faithful dog Argos:

“As they were talking, a dog that had been lying asleep raised his head and pricked up his ears. This was Argos, whom Odysseus had bred before setting out for Troy. … As soon as he saw Odysseus standing there, he dropped his ears and wagged his tail, but he could not get close up to his master [and] Argos passed into the darkness of death, now that he had seen his master once more after 20 years.” (Homer, Odyssey, Book 17) [1]

Half a millennium later, we find another heartwarming tearjerker in the loss of Peritas, Alexander the Great’s favorite dog. While the story is mentioned only by the first century Greek biographer and philosopher Plutarch, he tells us that, “It is said, too, that when he lost a dog also, named Peritas, which had been reared by him and was loved by him, he founded a city and gave it the dog’s name.” (Plutarch, Life, LXI.3) [2]

But life for dogs in ancient Greece wasn’t always so rosy. After the tragic death of the young Patroclus, sidekick to Achilles, against the Trojan hero Hector, we learn the fate of his hounds at his funeral celebration:

“Patroclus had owned nine dogs who ate beside his table. Slitting the throats of two of them, Achilles tossed them on the pyre.” (Homer, Iliad, Book 23)

Much as we learned last time in ancient China, dogs were favored by the Greeks as sacrificial victims for purification after death and birth. [3]

Despite the presence of dogs at the Trojan War, evidence in the Iliad and Odyssey suggests that the Greeks at the time of Homer primarily used dogs for hunting, shepherding, and guarding, not warfare. In fact, there’s scanty visual or literary evidence of the Greeks employing war dogs even through the Classical era. [4] The closest suggestions of war dogs comes to us through accounts not of the Greeks, but of the cultures to the east of Greece: Neo-Assyrian, Persian, Lydian, etc. As recorded in Aelian’s De Natura Animalia, we do find one potential Greek war hound memorialized in a mural in the Stoa Poikile in the Athenian Agora, who followed his hoplite master into battle against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. More likely, however, this was a faithful guard or hunting dog rather than a trained war dog:

Despite the presence of dogs at the Trojan War, evidence in the Iliad and Odyssey suggests that the Greeks at the time of Homer primarily used dogs for hunting, shepherding, and guarding, not warfare. In fact, there’s scanty visual or literary evidence of the Greeks employing war dogs even through the Classical era. [4] The closest suggestions of war dogs comes to us through accounts not of the Greeks, but of the cultures to the east of Greece: Neo-Assyrian, Persian, Lydian, etc. As recorded in Aelian’s De Natura Animalia, we do find one potential Greek war hound memorialized in a mural in the Stoa Poikile in the Athenian Agora, who followed his hoplite master into battle against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. More likely, however, this was a faithful guard or hunting dog rather than a trained war dog:

“An Athenian took with him a Dog as fellow-soldier to the battle of Marathon, and both are figured in a painting in the Stoa Poecile, nor was the Dog denied honour but received the reward of the danger it had undergone in being seen among the companions of Cynegirus, Epizelus, and Callimachus. They and the Dog were painted by Micon, though some say it was not his work but that of Polygnotus of Thasos.” (Aelian, De Natura Animalia, vii. 38) [5]

A particularly stunning representation of hounds in action is seen on the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. This is not the sarcophagus of Alexander the Great. Rather, it depicts Alexander in the Battle of Issus on one side and a lion hunt on the other. Interestingly and supporting the scanty evidence of the Greeks using dogs in warfare, the hounds depicted on the sarcophagus appear only in the hunting scenes.

As today, dogs in classical antiquity appeared in many breeds. Ancient authors and inscriptions give us the names of some of these breeds. Native to Greece, the swift Laconian or “Spartan” breed was well regarded for its hunting prowess. Far heavier and ideal as a sturdy guard dog or hunter of large game was the Molossian, possibly an ancestor to the modern mastiff. And the Cretan was supposedly a crossbreed of the Laconian and Molossian. That’s Cretan, not cretin. Big difference. As for non-Greek breeds that the Greeks enjoyed, the Celtic Vertragus, with its lean, sleek features, is often cited as an ancestor to the modern greyhound.

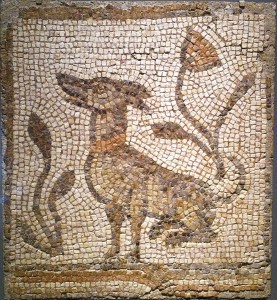

Now, I’m not a card-carrying American Kennel Club certified dog show judge, but when I look at this mosaic in the Art Institute of Chicago, I see many of the features that the Greeks admired in the Vertragus breed. Around AD 150 in his Cynegeticus (a treatise on “Hunting with Dogs”), the Greek military historian Arrian wrote that Vertragus dogs:

Now, I’m not a card-carrying American Kennel Club certified dog show judge, but when I look at this mosaic in the Art Institute of Chicago, I see many of the features that the Greeks admired in the Vertragus breed. Around AD 150 in his Cynegeticus (a treatise on “Hunting with Dogs”), the Greek military historian Arrian wrote that Vertragus dogs:

“…in figure, the most high-bred are a prodigy of beauty; — their eyes, their hair, their colour, and bodily shape throughout. Such brilliancy of gloss is there about the spottiness of the parti-colored, and in those of uniform colour such glistening over the sameness of tint, as to afford a most delightful spectacle to an amateur of coursing. (III.7) …

[They should] be lengthy from head to tail; for in every variety of dog, you will find, on reflection, no one point so indicative of speed and good breeding as length; … [with] light and well-articulated heads. … Their eyes should be large, up-raised, clear, strikingly bright. The best look fiery, and flash like lightning, resembling those of leopards, lions, or lynxes. (IV.5) … Let the ears of your [vertragi] be large and soft, so as to appear from their size and softness, as if broken. The neck should be long, round, and flexible … tails fine, long, rough with hair, supple, flexible, and more hairy towards the tip. (V)” (Arrian, Cynegeticus) [7]

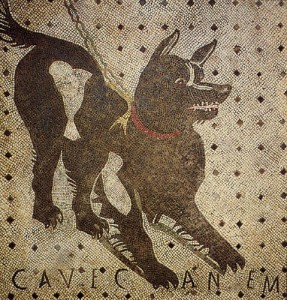

Ancient authors tell us that getting a large guard dog is the first thing a farmer should do. “Never, with [a dog] on guard,” says Roman poet Virgil, “need you fear for your stalls a midnight thief, or onslaught of wolves, or Iberian brigands at your back” (Georgics, III.404ff) Though some authors are sure to point out that you ought make sure the dog was trained by a shepherd rather than hunter, so it’ll guard the sheep rather than chase the rabbit. A white dog is best for the shepherd, so you may see it clearly at night, while a black dog is ideal for the farm to terrify thieves in day and for stealth in darkness.

Ancient authors tell us that getting a large guard dog is the first thing a farmer should do. “Never, with [a dog] on guard,” says Roman poet Virgil, “need you fear for your stalls a midnight thief, or onslaught of wolves, or Iberian brigands at your back” (Georgics, III.404ff) Though some authors are sure to point out that you ought make sure the dog was trained by a shepherd rather than hunter, so it’ll guard the sheep rather than chase the rabbit. A white dog is best for the shepherd, so you may see it clearly at night, while a black dog is ideal for the farm to terrify thieves in day and for stealth in darkness.

Arrian wrote the aforementioned Cynegeticus as something of a supplement to an earlier treatise on dogs also entitled Cynegeticus written by Xenophon in the late 5th or early 4th century BC. Xenophon tells us that we should “give the hounds short names, so as to be able to call to them easily.” [8]  A few of the names he suggests include Dash, Rover, Sparky, Killer, and Blossom (in order, that’s Ormé, Poleus, Phlegon, Kainon, and Antheus). If you want to see the whole list, I’ve published a table of about 50 ancient Greek dog names mostly from from Xenophon’s Cynegeticus written in Greek and Latin scripts as well as their approximate English equivalents. You’ll find that list online at ancientartpodcast.org/dogs. Sometimes I’ve taken some interpretive liberties with the English equivalent. When browsing the list, if you have a suggestion for a more accurate English name, please leave a comment or shoot me an email at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

A few of the names he suggests include Dash, Rover, Sparky, Killer, and Blossom (in order, that’s Ormé, Poleus, Phlegon, Kainon, and Antheus). If you want to see the whole list, I’ve published a table of about 50 ancient Greek dog names mostly from from Xenophon’s Cynegeticus written in Greek and Latin scripts as well as their approximate English equivalents. You’ll find that list online at ancientartpodcast.org/dogs. Sometimes I’ve taken some interpretive liberties with the English equivalent. When browsing the list, if you have a suggestion for a more accurate English name, please leave a comment or shoot me an email at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

But not all dogs in the classical world were bred for sport or duty. Supposedly originating from the island of Malta, the Melitan was a small, long-haired, short-legged lap dog. Evidence suggests that small dogs, although not new, came to be favored during the Roman period, particularly in Roman Britain.

But not all dogs in the classical world were bred for sport or duty. Supposedly originating from the island of Malta, the Melitan was a small, long-haired, short-legged lap dog. Evidence suggests that small dogs, although not new, came to be favored during the Roman period, particularly in Roman Britain.  This might signify a shift in attitude toward ownership of dogs as pets rather than solely the traditions of hunting, herding, and guarding. This shift could also betray the taste for conspicuous consumption among the Roman elite, where one could afford the expense of small, showy, “non-utilitarian” pets. [9]

This might signify a shift in attitude toward ownership of dogs as pets rather than solely the traditions of hunting, herding, and guarding. This shift could also betray the taste for conspicuous consumption among the Roman elite, where one could afford the expense of small, showy, “non-utilitarian” pets. [9]

Perhaps the most famous dog from Greco-Roman antiquity is Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog at the entrance to Hades, the underworld. As we learned in the first of our three episode on “Dogs in Antiquity” when we explored the hairless dogs of the ancient Americas, dogs hold prominent places as emissaries of the dead and guides for the soul … or to use the fancy Greek word, “psychopomp.” [10] With the ancient funerary effigies of the Colima culture from West Mexico, the form of the dog would often be altered or enhanced with a double body, turtle shell, human face, or some other transmutation. Did this serve to grant the canine emissary greater spiritual power while also evoking a deliberately supernatural or otherworldly guise? It seems, then, perhaps not too far fetched to see a similar rationalization for granting three heads to Cerberus.

If you want to read more about dogs in the Greco-Roman world, be sure to browse the footnotes of this essay, where you’ll find a good number of additional resources. One of those good resources is the article “Dogs in Ancient Greece and Rome” in the Encyclopaedia Romana website, hosted by the University of Chicago. You’ll also find a fair number of references there for additional reading. [11]

If you dig the Ancient Art Podcast, be sure to “like” us on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and give us a nice 5-star rating on iTunes. You can follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston and can subscribe to the podcast on YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo, where you’ll hopefully give us a good rating and leave you comments. You can also email your questions and comments to me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or use the online form at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. Thanks for visiting the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2014 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[2] James Grout, “Peritas,” Encyclopaedia Romana.

[4] E. S. Forster, “Dogs in Ancient Warfare,” Greece & Rome, Vol. 10, No. 30 (May 1941), pp. 114-117.

[6] James Grout, “Dogs in Ancient Greece and Rome,” Encyclopaedia Romana.

[7] Arrian, On Coursing (Cynegeticus), Trans. J. Bohn, London, 1831.

[11] James Grout, “Greek and Roman Dogs,” Encyclopaedia Romana.